AboutEssays1991Celebrity

In the immediate wake of 9/11, Daily Mirror editor Piers Morgan hastily declared an end to The Celebrity Culture. His polemical wager centred on the dawn of a new age of serious thinking. It cut directly against the grain of tabloid thinking and effectively signed his own newspaper death-knell, as The Mirror’s sales fell directly into freefall.

Ignore The Celebrity Culture at your peril. Celebrate it with caution. Attempt to defy it and you will hastily become enveloped by its Faustian embrace. Seven years after declaring its end, with an irony arch enough to drive a double-decker bus under, Piers Morgan is a central figure in Britain’s Celebrity Culture. He makes his living mostly as a judge on The Celebrity Culture’s favourite medium, reality TV shows, and interviewing celebrities for a glossy magazine. Soon he will consolidate his own niche in The Celebrity Culture, replete with the requisite spray tan and teeth whitening signifiers, by hosting a chat show in which one self-made Celebrity of the age will talk to others. His brassy soundbite, so potent in the eye of international tragedy, meant nothing after all.

At the risk of glibness, just as the words were dropping out of the Editor’s mouth, 9/11 was confirming temporary celebrity status on previously unfound icons. The good. The Mayor of New York, the Head of The Fire Department, individuals showing previously unseen displays of bravery and heroism. And the darkest celebrity of them all: ‘the baddie’. Bin Laden’s celebrity was such that a distant relative of his became a momentary newspaper obsession herself in the UK two years later, simply on the strength of sharing his surname.

The Celebrity Culture endeavours to keep a moral temperature between good and bad, but as it twists through the national psyche – encompassing such unlikely candidates as ‘The Canoe Wife’ who hid her husbands identity from her children, the lapdancer who the comedian informed her grandfather he had fucked live on national radio, the nurse who dated the TV presenter on a rape trial, a multiplicity of footballer’s spouses and a pantheon of young folk for whom fame constitutes a dream in itself – it bestows its arbitrary 15 minutes with slapdash abandon.

The Celebrity Culture was not about to go down in the aftermath of the fall of the Twin Towers. It had already acquired too much personal significance for a nation that had bought into the idea of the self as brand. It had begun developing its own serious agenda, becoming at once synonymous with the idea of personal identity and community empathy. (Go on. Start an argument in the pub. Say the words ‘Victoria Beckham.’ Everybody cares, one way or another).

The Celebrity Culture satisfies a deeper need for a narrative we can all share, a story in which reward for the good and judgement for the bad becomes modern folklore. These stories of the most public beacons of our age frame the moral temperament of the nation. They are stories of redemption and absolution. They satisfy age-old hopes that justice will be done and that the good guy will get the girl and eventually save the world.

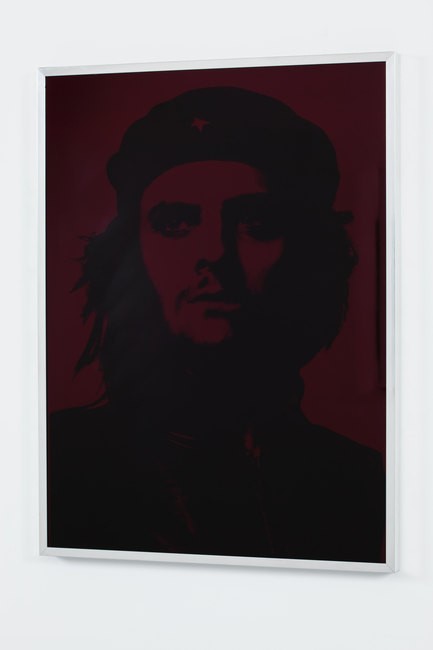

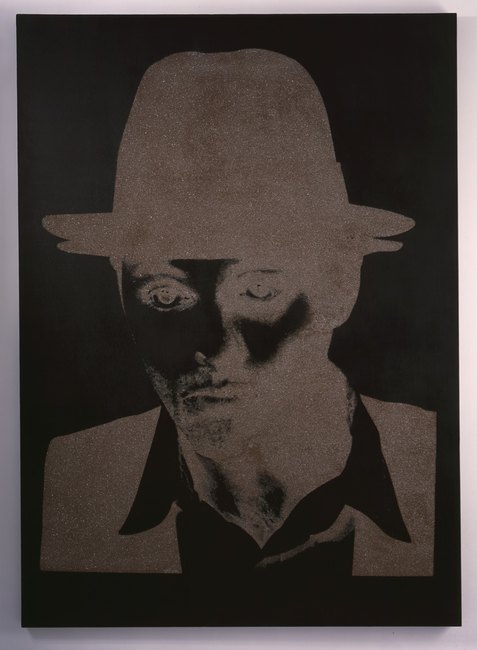

In this way, there is an argument for the case that The Celebrity Culture is the most honest arbiter of the time we live in. The psyche has become a modern instrument to be mastered. Playing it and shaping it is its own talent. Those living in the bookmarks between reality and celebrity have become living works of art. We can point at them and adjudicate ourselves against them.

One of the most fun aspects of a Celebrity Culture that embraces not just the extraordinary but the ordinary in extraordinary circumstances is that we can measure how we might behave in a similar predicament. The Celebrity Culture as it stands is embodied in a South London dental hygienist that became one of the most recognisable names in the country after three months of public vilification in the Big Brother house, a subsequent turnaround, a further public shaming and redemption through illness. She is the first woman that has lived her entire adult life and may well die in the full public glare. Even her name feels weirdly symbolic or ironic, depending on the public’s mood towards her at any given moment, as if to prove that ‘Reality’ and ‘Celebrity’ have conspired to become the Dickensian fable of our times. Start a fully blown pub fight. Say the words ‘Jade Goody’. Everyone cares, for better and for worse.

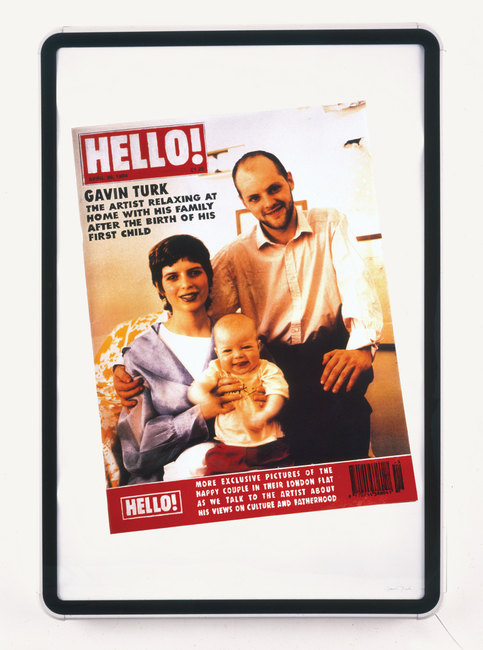

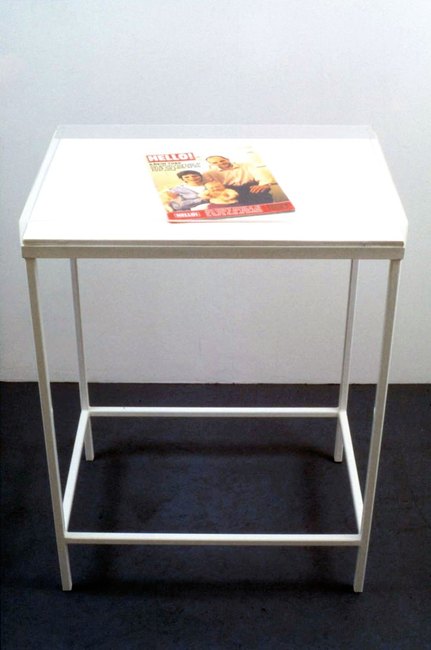

A graph point somewhere between ‘Celebrity’ and ‘Reality’, not yet named, has become the esoteric watchword of our era. The Celebrity Culture itself has replaced The Fairy Tale as the modern day fabulisation of moral and social codes. Heat, OK!, Hello and the daily coverage of The Celebrity Culture’s superstars in the tabloids and beyond act as its very own Hans Christian Anderson.

One of the most recognisable Fairytale narratives is that of ‘rags-to-riches’. But the pot of gold at the end of the modern rainbow is not only about money, however much the deification of cold and charismatic businessmen Alan Sugar, Roman Abromavich and Simon Cowell might suggest otherwise. In a fractured social state, validity is reached through remuneration <and> recognition. A side order of both remains The Celebrity Culture’s holy grail. The glamour model Katie Price, or Jordan in her Fairy Tale Princess guise, has become the most significant beacon of the acquisitive modern urge for both. The reason young girls look up to her more than other icons of her generation is a complicated combination of business acumen, show-and-tell shamelessness, an implicit understanding of the demands of her epoch and simply fulfilling the affably sexual, game-lass role in culture that calls to mind anyone from Diana Dors to Samantha Fox – those Fairytale princesses of yore, both beacons of an older, more innocent incarnation of The Celebrity Culture.

Within Jordan’s and Goody’s stories and with all the Princesses that try their hand at living this year’s model of the Fairytale, a democratisation of Celebrity has taken place. In an age where the self has become the centre and mass communication fulfils the grand Warholian prophesy to the letter, Fame has become something that is no longer about People Like Them. It is about People Like Us. Public recognition has become about personal recognition. The cycle completes itself. Fame for everyone and everyone for fame. If there is an element of narcissism in not wanting Celebrities to be elevated and choosing to take them Just Like Us, then it is counterbalanced by the needling reality that it presents hope for everyone. And who doesn’t really want that?

The Celebrity Culture has now delivered its own hard-edged appeal. A collective game of good vs evil has emerged within it. So Fairytale! Sorry to hark back, but no-one quite fulfils these age-old tales with more tenacity and slyly intuitive public exuberance than Mrs Beckham. Her transformation from pock-marked, flat-haired, unremarkable Spice Girl to aerodynamic fashion plate has been a stealthy Ugly Duckling anecdote for our times. And there was her handsome Prince, waiting patiently and compliantly, to conduct her down the aisle in a chariot of gold, paid for in an unprecedented deal by The Celebrity Culture’s favourite magazine. Before long her happily-ever-after is interrupted by Rebecca Loos, who instantly slips into the role of the dragon that needs to be slain by the withering, icy disapproval of the public. In The Celebrity Age silence has become the most potent weapon of choice against interrogation. It has invested the blonde model, the graffiti artist and the author of her generation with their own modern superpower. So Mrs Beckham follows the lead of Moss, Banksy and Rowling and keeps schtum on her husbands infidelity, styling out the impasse with a gravity that is both distinctly old fashioned and uniquely modern. Letting us be the judge. Clever girl.

In an age of transparency, where every aspect of the art of living has its price, to be auctioned off in an insane Sotheby’s of the psyche, silence is the only tool left to keep a myth in tact and protect a fantasy of living the perfect life. At the other end there is the serial confessor. Tracey Emin has removed any sense of enigma or mystery about her life by revealing it down to every last artful detail. In The Celebrity Culture, the public has chosen the role of priest in the confessional. We still await Amy, Britney and Kerry to say their rosaries.

To lend Mrs Beckham’s Fairytale ending a strange intertextual twist, Loos’ final public dressing down after public rejection was delivered by another formerly betrayed wife (Sharon Osbourne) who had entered the public faculty and The Celebrity Culture by way of a reality TV show (The Osbournes), on a reality TV talent contest (Celebrity X Factor) in which ‘real’ celebrities imitated the motives of the ‘hopeful’ celebrities of Saturday night light entertainment. Did the whole hall of mirrors come crashing down after this? Of course not. It simply ripped up another chapter of The Modern Book of Fairytales and started over the process of replication, this time with another footballer, Ashley Cole, and another rags-to-riches reality Princess, Cheryl Cole, feeding the public need to cast villains and victims and deify the righteous.

Is modern day Celebrity any worse than Fairytales of old in presenting unrealistic ideals? Or is it just a more complicated variant of the same? No matter how much a Celebrity chooses to control their own myth, no matter how much they shroud it in mystery or unknave themselves completely for public consumption, the judgement is left to the moral hordes. Who stays and who goes? We decide.

The Celebrity Culture is just a filter, a storytelling exercise, a picture book to turn the pages of and come to conclusions about the deep seated sense of right and wrong, good and bad, that has always been passed down from generation to generation in one form or another. Same as it ever was.

So rest assured.

Night, night and God bless.

Good, in the end, will always triumph over evil.