AboutEssays1993Eggs

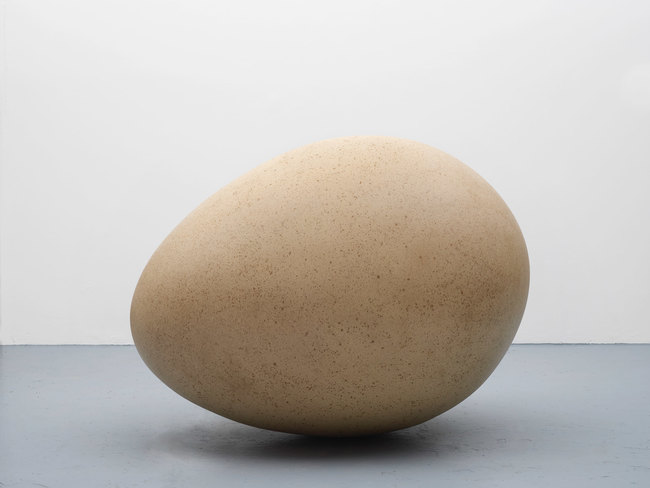

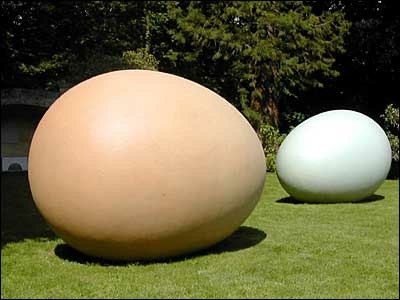

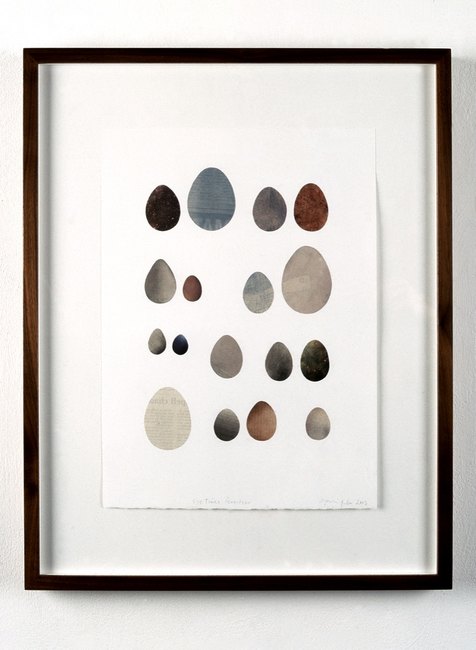

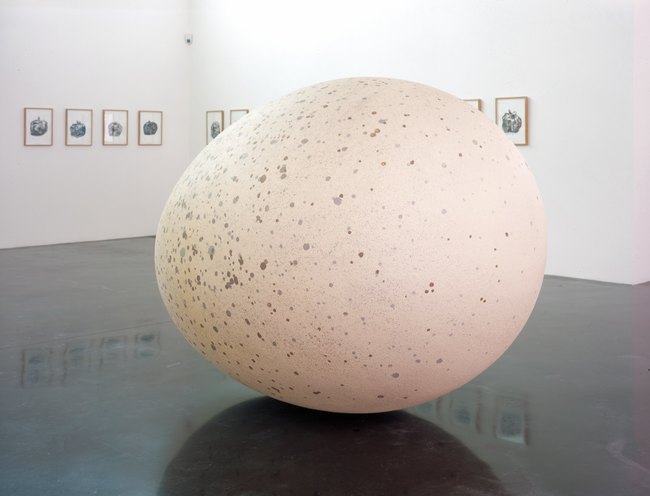

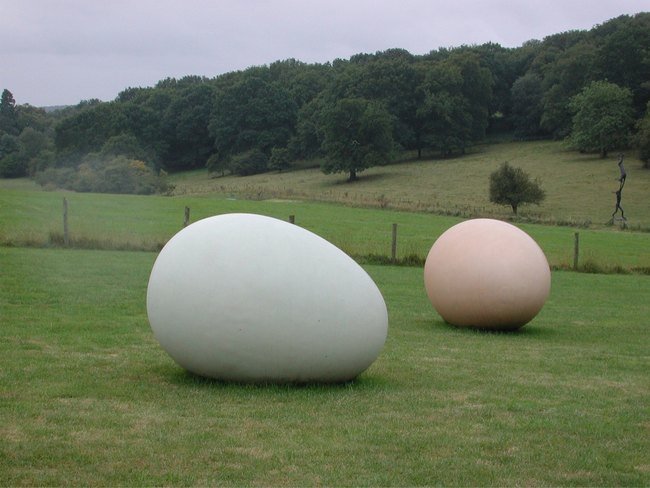

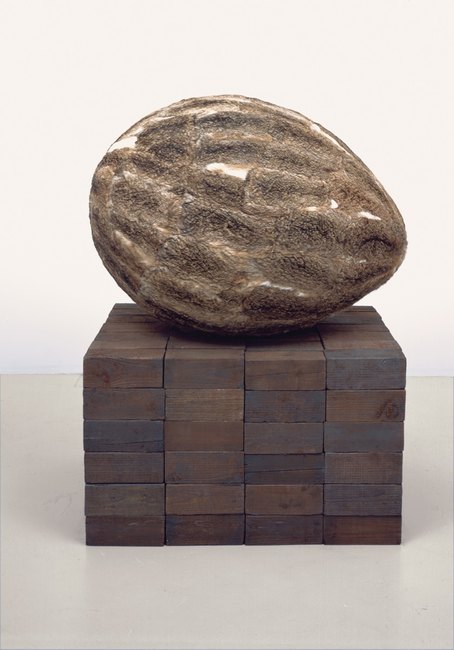

Eggs incarnate pure balance. Their harmonious simplicity of form is only rendered more poignant by their function: they hold and protect life. The strength of the shell that harbours the makings of a living creature is all the more impressive because although it can withstand surprising levels of pressure – the egg of the ostrich is reputed to support up to 20 stone – it can not resist the impact of a drop or a knock. Once the ovoid shape has been cracked by an external force, the life it was meant to protect no longer exists. Once it is broken from the inside, this life begins. Although the shell itself is made of minerals, essentially calcium, and can sometimes have the rough texture of a stone, it also has thousands of pores through which oxygen can get to the embryo.

The nurturing virtues of the egg have carried over to various cultural beliefs. Although eggs are most often perceived as tokens of affection, exchanged as an expression of love by the Alsatians or used to announce the forthcoming birth of a child by the Chinese, they are sometimes destroyed as a form of protection. Indeed, the Romans crushed their shells in their plate to ward off evil. Many other cultures have later adopted the tradition in the belief that witches could use intact shells as boats on which to navigate at sea in order to sink other vessels.

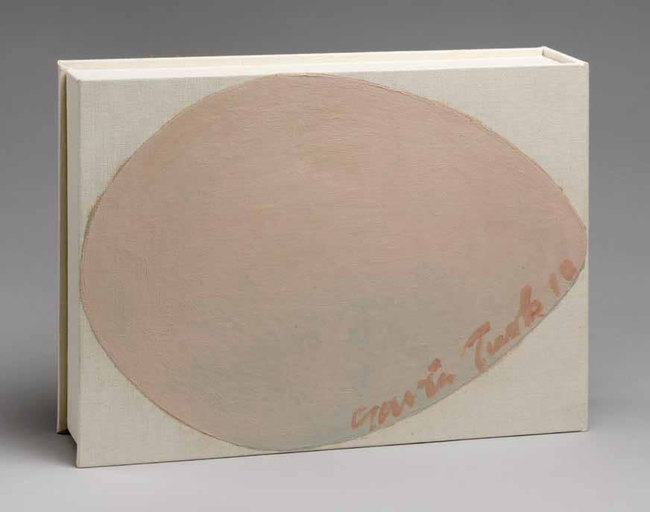

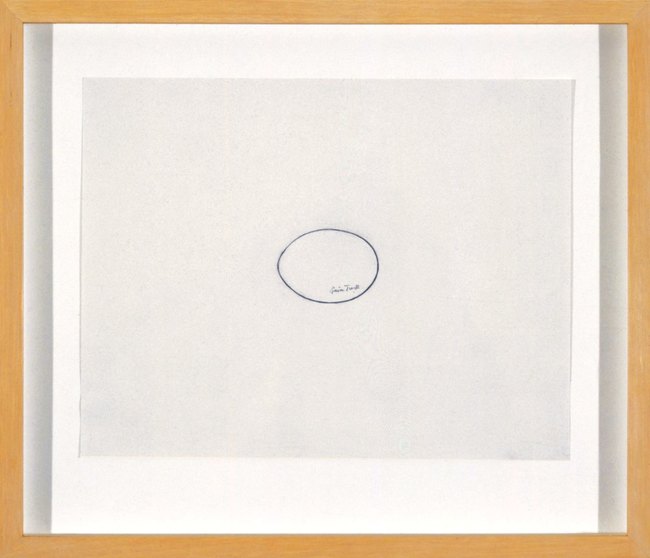

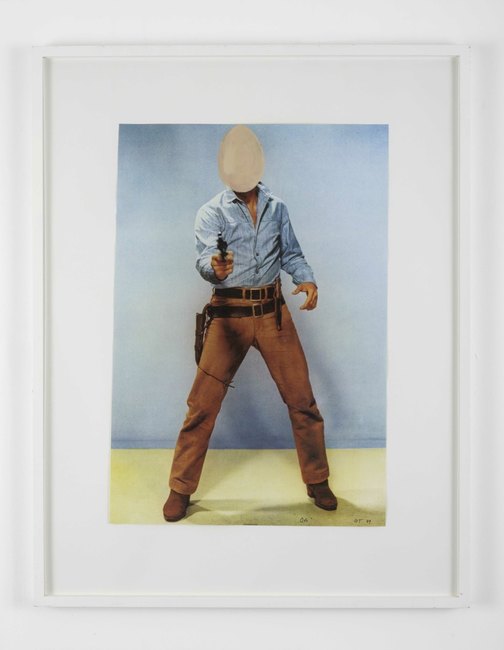

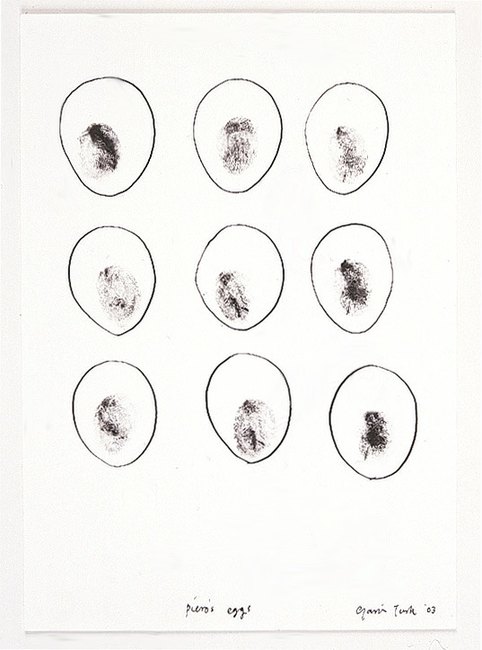

Art appropriates the egg as a material for painting (egg tempera) as well as a basic form that conveys certain ideas of femininity, maternity and protection. When I was a child, my father was given a bronze sculpture of a giant egg which is in fact a self-portrait by Salvador Dali. Indeed, the egg is cracked and through this fissure sprouts a twisted lock of hair, the infamous moustache and an eye of the artist, forever struggling to hatch. Symbolising both birth and inspiration, this work uses the egg as an emblematic origin for the artist and his genius.

It is no coincidence that a number of mythical characters originated from eggs. Legend has it that Castor and Pollux, the sons of Leda and Zeus came into the world out of eggs. Rather fittingly, the birth of Eros, God of Love, is sometimes spectacularly described as a hatching:

“Of Darkness an egg, from the whirlwind conceived,

Was laid by the sable plumed Night.

And out of that egg, as the seasons revolved,

Sprang Love, the entrancing, the bright,

Love brilliant and bold, with his pinions of gold,

Like a whirlwind, refulgent and sparkling.” (Aristophanes, The Birds)

The egg itself is most often an unassuming, familiar object but it can sometimes aspire to the status of work of art when it is decorated. Of course, the Easter egg painstakingly adorned with wax and vegetable dyes is perhaps the most familiar version but it comes as no surprise that the Romanov Russian imperial family established an upscale take on this tradition during the nineteenth century. The obscenely precious jewelled eggs that Carl Fabergé fabricated for them to exchange on special occasions might not have concealed a life but certainly held a wealth of surprises: clocks, jewellery and miniature replicas of palaces. Although eggs are usually rather modest symbols, the Fabergé egg highlights their wondrous side: that out of such a modest and simple thing can spring the most precious and mysterious gift, whether is a jewel, inspiration or life itself.