AboutEssays1994Scary Monsters Performing

I only ever saw one performance by Gavin Turk. He came on stage and shat a string of sausages to the sound of Scary Monsters. Of course every exhibition private view is a strained performance by everyone present. In After Theory Terry Eagleton writes about our increasingly self-conscious performance of temporary selves. How we now accept a loosely connected relationship to whatever self it is we're supposed to be performing, as opposed to a previous era of modernity when more repressed and un-self-knowing types suffered endless traumatic shocks from the realisation that a persona is precisely not a real self.

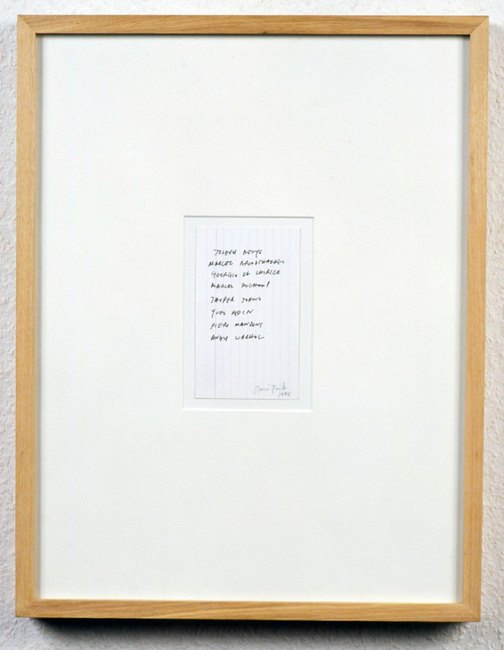

Artists who performed an artist-role in the past include Marcel Duchamp and a lot of European figures whose names I can't remember; one I never know what the sex is: you see those photos of her or him all the time, from the 1920s. Claude Calhoun? Then there's Piero Manzoni, Yves Klein and Marcel Broodhauers: the mythic Euro-proto-conceptual-art figures that Gavin often invokes. The last one died of stomach cancer; having been a great gourmet he couldn't enjoy eating anything at all for a long period before he finally caved in. Both Manzoni and Klein died very young, barely thirty; Klein from a freak heart attack, Manzoni the same, caused by over eating. Manzoni signed boiled eggs with his thumb. He signed cans of his own excrement. "Excellent!" he said -- "I think I’ll call it Artist's Shit!"

Every artistic self-portrait is a performance of a certain kind, obviously not a profound one: the profundity is in the achievement of the work as a work, on its own terms, more than in the success or failure of the performance as such. But a Rembrandt self-portrait is always a kind of staging of the profession of "artist" -- what do they do? Their job is to look. You're very aware of how light falls in his Self-portrait at Age 63 in the National Gallery, and how forms relate: those are the key skills for a painter in those days. When he dresses up it's to elevate the status of the skills: they deserve a bit of grandiosity he's saying. He dressed up in his period of commercial success more than in his period of commercial decline. We believe he gets more honest but it's more that he gets older.

The description of a face aging is moving, and so is the incredible skill with which it's done.

When Duchamp performs for photos, whether it's by Man Ray or whoever it was, so the photo is an artwork about a shifting sense of self, it's not to tell you what an artist is but to tell you something about how meaning works. When Gerhard Richter tells you about meaning in photos by painting a photo so that it has the allure of a photograph but is obviously only a painting, Richter himself remains this rather boring character which he is in real life. When Duchamp is photographed as a woman the whole idea of Duchamp as a figure becomes intimidating, impressive. He makes all these intuitive moves. It's surprising how lo-tech his whole act is, how little there is to it, how scruffy his objects are, how anyone could have done them. They're all about staging some kind of inroad that meaning makes into art, with the figure of The Artist like some constant slightly disturbing dream you wake up from, anxious that there's something you ought to remember. The message is about changing conditions in society, mass production, industry, the different ways in which art is now spot-lit, ritualised and celebrated. Light is cast onto art so it can cast light on everything else. How did we used to see it? In a court or a cathedral or a private chapel, then in the Salon, and then in salons organised by literary lesbians and rich Russians and so on, and now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but before that in some store room prior to the Armoury Show: "Hey there's a urinal." "Chuck it out!" "OK."

Obviously Matthew Barney's imagery is great. It's the filmic timing that's wrong, the lumbering, non-Rembrandt blind grandiosity. It's A Knockout giants with ginger beards crossing the sea endlessly to Orkney; dressed-up poseurs taking far too long to pretend to be sperm. How are you supposed to respond? A black and white photo of Manzoni signing an egg with his thumbprint: now that's show business!

What kind of a figure should an artist be? Many of the YBAs have had a stab at this problem, the top ones perhaps with the least success in Duchampian terms: that is, instead of interrogating meaning they keep trying to make themselves seem like Arthur Rimbaud. Someone shrieking on Big Brother is the same as Tracey Emin shrieking outside Munch’s house, there’s no difference at all in depth of feeling. (She made a film in 1999 of herself nude screaming on a wooden jetty outside Munch’s summer house, called Homage to Edvard Munch and all my dead children.) Someone getting depressed on Big Brother is the same as Emin being depressed. But unlike them she produces a lot of slogans about it – You forgot to kiss my soul – My cunt is wet with fear – Every part of me is bleeding - Exorcism of the last painting I ever made -- and sometimes makes them into needlework: the depression still isn’t interesting but the pleasure of the art object is. When these slogans or sound bytes are made into neon signs like Nauman’s, or videos like Acconci’s, or driftwood sculptures like arte povera or little gouaches or oil paintings by any art-world Me-Too striver, it’s possible to feel impressed by the confidence but at the same time completely unengaged emotionally.

The artist's real unmade bed transposed from the private space of the bedroom to the public space of the gallery, but otherwise untransformed. What is it? A manufactured saintly relic: the great power it memorialises or stands for is St Pain, St Class, St Gender, St Femininity, St Abjection and St Ethnicity (English mother, Turkish father) and of course St Victim. Her devil muses are Drunk, Raped and Can’t Spell. The popular audience receives all this simply as glamour – simplicity is pretty powerful. For this audience (as expressed in a sublime moment in Spinal Tap when the band’s manager tries to sum up ideology) the operating notion when it comes to loving Emin is that we live in a sexy world or maybe a sexist one, and art like hers exists on some kind of edgy interface between the two.

In a book of interviews Damien Hirst and the writer Gordon Burn perform a kind of authenticity act, each outdoing the other in macho talk. "Grr" is the basic sound all the way through. "Fucking fuck!" "I fucking thought fuck that!" "Yeah fuck that fuck." "Death fuck." The design follows the rough fuckiness of the apparently coke-fuelled fake frenzy of honesty. The illustrations are grainy and look like they might have just fallen on the page with a load of post-it notes. (Album covers used to sometimes stage this look). This method-acting of meaning -- the combination of shouting out impulsive imitations of truth for hour after hour because you're so fucking crazy that finesse or politeness is just fucking bullshit for phonies, with illustrations of artworks that aren't arranged in a coldly glossy way like advertising but have a calculated designer wonky graininess instead -- is different to the feel of Hirst's actual work, which is always factory finessed, and is in fact very like advertising. As if cold distance, a total lack of anything meaning anything, occasionally needs a bit of direct raw meaning in the picture so you can see more clearly what the meaning of true meaninglessness really is.