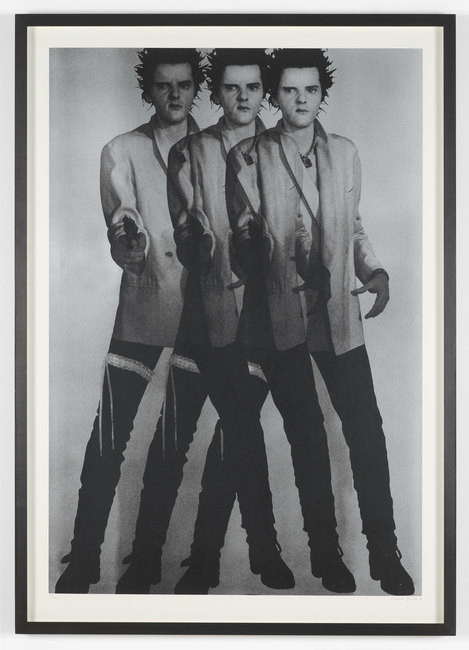

AboutEssays1999Sid Vicious

In every generation there are the brave ones: the artists, stylists, intellectuals, the street kids who heedlessly launch themselves into the future, who refuse to be trapped by what is known. Within this small group, there is always a figure who doesn’t necessarily produce very much, if anything at all, but whose whole presence defines his or her time and place.

Their every gesture, captured in a photograph or on film, appears to sum up the spirit of an era. In the late 1920’s – the era of the Bright Young Things – it was androgynous socialite Stephen Tennant. In the Warhol Factory it was the elfin, amphetamined Edie Sedgwick, who danced the high wire with consummate grace. In British Punk, it was Sid Vicious.

Sid could have been the front man of the Sex Pistols – and eventually was. He was one of the four Johns – Lydon, Wardle, Beverley and Grey: herberts all from North and East London - who crashed down the Kings Road during 1975, sneering at everything in sight. When McLaren decided to hold an audition for the fledgling “Sex” group, Sid was absent. His friend John Lydon got the call.

Unhappy about this turn of events, Sid became the Sex Pistols ur-fan. He began to get attention for violent behaviour. He was one of the Sex Pistols’ entourage involved in the famous, photographed fight at the Nashville in April 1976. He assaulted rock journalist Nick Kent, and was implicated in an incident at the 100 Club where a glass was thrown and a girl badly injured.

He was, after all, called Sid Vicious. In later years, Lydon would downplay his involvement in what turned out to be the creation of a monster. Sid was known under a couple of names – John Beverley and Simon Ritchie - but sometime in 1974 or 1975, in the spirit of pop re/creation, Lydon gave him a new pseudonym: Sid after his hamster, and Vicious after the song by Lou Reed.

It was a joke, a laugh. But re/creation is an unpredictable undertaking. In the Warholian ambience of early London punk, Vicious was a leading character: his name offered him a fast-track to fame, if not notoriety. By the time that the music press began to run features about Punk as something more than just a couple of rock groups, Sid was highlighted as an avatar of this new, troubled age.

In Jonh Ingham’s seminal October 1976 Sounds article, ‘Welcome to the “?” Rock Special’, Sid dominated the pull quotes: ‘I didn’t even know the Summer of Love was happening. I was too busy playing with my Action Man’; ‘I don’t understand why people think it’s so difficult to learn to play guitar. I found it incredibly easy. You just pick a chord, go twang, and you’ve got music’.

And there was more: ‘I don’t believe in sexuality at all. People are very unsexy. I don’t enjoy that side of life. Being sexy is just a fat arse and tits that will do anything you want. I personally look upon myself as one of the most sexless monsters ever’. In the end was a kind of manifesto: ‘I’ve only been in love with a beer bottle and a mirror’.

Sid’s comments were a mixture of posturing and candid revelation. They introduce him as a character not afraid to take the limelight, with a catchy – if slightly ludicrous: Sid after all was redolent of the 1920’s – pseudonym that seemed to match the half-serious, half- joking brutality of early Punk. Violence was both theatre and tool: to clear space, to reproduce the ambience of England in 1976.

Unlike the moronic monster of legend, Sid was very sharp, as his friend Viv Albertine remembers: ‘I always felt very uncomfortable with him he was so strict, and so idealistic, and so clever, which people don't seem to realise. The reason he went scooting downhill, he was so idealistic, and he really couldn't stand the world and its pettiness’.

I first encountered Sid in November 1976, at a Clash show at the Royal College of Art. Standing at the front, I became aware of this person standing next to me, swaying and strutting. I kept watch on him, and was not surprised when he got up on stage, sharing Joe Strummer’s mike, and threatened the students who were busy showering the Clash with beer glasses.

His threat was blunt and to the point: ‘c’mon cunt and I’ll do ya’. It is this brutal earthiness that characterises Sid’s verbal pronouncements – before his persona and the drugs took him over. In the summer of 1977, he gave an excoriating interview to Fred and Judy Vermorel: ‘I think that largely they’re scum and they make me physically sick, the general public. They are scum’.

By that time, he had become a Sex Pistol. The selection had been made not so much on musical ability – although Sid could play Ramonic bass lines well enough – but on his persona and his friendship with John Lydon. He looked like a Sex Pistol and, as the other three members of the group began to withdraw from all the media attention, he began to take centre stage.

His slow and wracked downfall was conducted in public. Part of Sid’s problem – which is also the reason for his iconic status – is that he followed a bad idea all the way. He was in love with the New York punk ethos than ran from the Velvets to Lou Reed to the New York Dolls and then Richard Hell and the Ramones: that’s where Nancy Spungeon and the hard drugs came from.

The photographer Roberta Bayley befriended him during the Sex Pistols’ January 1978 tour of the US, when Sid was going cold turkey. The climactic show of the tour occurred at San Antonio in Texas, when the band played under a hail of material thrown by the local rednecks: Sid took up the challenge, and clubbed a sample member of the audience with his bass.

As far as Sid was concerned, he was the only one of the band who had stood up to the cowboys. He was the true Sex Pistol. But the expectation of his name was all too much. ‘I was sitting with him at the soundcheck,’ Bayley remembers; ‘He said “I wanna be like Iggy and die before I’m thirty,” and I said: “Sid, Iggy is over thirty and he’s still alive, you got the story wrong’.

A week later, the Sex Pistols broke up and Sid was in Jamaica Hospital after an overdose on his flight from LA. He was all alone, and reflective when Bayley called him up: ‘I’ve got six months to live’, he tells her. ‘Oh well don’t drink. You asshole’. ‘I’ll end up burning myself out’. ‘But what will you do if you go back to London? The same thing?’ ‘Yeah, I probably will die in six months actually’.

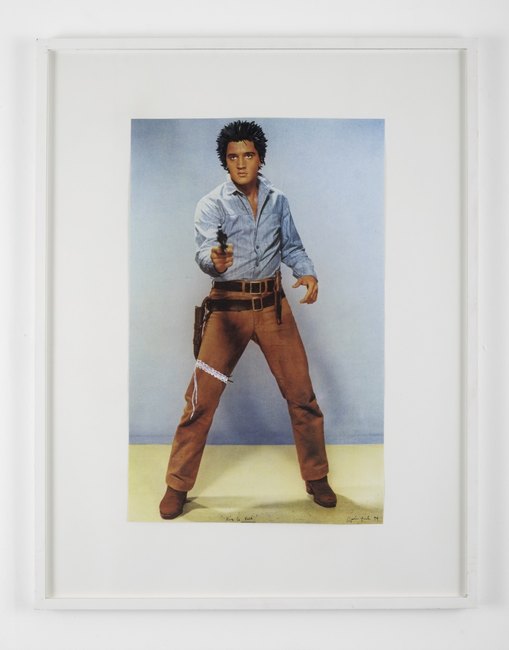

Sid’s self-destruction cast him as an archetypal Romantic hero and the embodiment of London Punk’s headlong, heedless momentum that in 1978 was on the point of burn-out just as it was becoming mainstream pop. After John Lydon abdicated, so Sid became the singer: fronting on “My Way” and the group’s two best sellers of the 1970’s, “Somethin’ Else” and “C’Mon Everybody”.

These Eddie Cochran covers recast Sid as the archetypal ‘Too Fast To Live, Too Young To Die’ rock hero. This had been one of McLaren’s names for the shop at 430 Kings Road, and the Sex Pistols’ manager remained in love with the nihilistic, primal drive of fifties rock’n roll. As filmed in “My Way”, Sid was the young gunslinger, the fanatical assassin out to murder a world.

There was a human being under this: one who did not have much of a chance. The most disturbing moment in “My Way” comes when Sid shoots a middle-aged woman: the idea was that this was not only a representative of the hated hippie generation, but also Sid’s mother, Anne Beverley – the woman who bought the heroin that would kill him in February 1979.

In the Vermorels’ interview, Sid locked into one of his characteristic rants: ‘Grown-ups have just got no intelligence at all. As soon as somebody stops being a kid, they stop being aware. And it doesn’t matter how old you are. You can be 99 and still be a kid. And as long as you’re a kid you’re aware and you know what’s happening. But as soon as you “grow up”….’

Sid never grew up. In all his spectacular crash and burn, there was not much that was not the action of a child. This concentration on child-like awareness had, ironically, been one of the hallmarks of the hippies, and had – in the hands of leading exponents John Lennon (“Strawberry Fields Forever”) and Syd Barrett (“Mathilda Mother”) had been just as redolent of emotional damage.

But then Sid also did it to himself. He bought the script, much of which was already a cliché by the time that he was living it. How wearing was that New York junkie style, that blind sense of Rock ’n' Roll entitlement – with the black clothes, leather trousers, and sunglasses after dark. You’d avoid those people on the street, not because they were dangerous, but because they were boring.

Even so, there was something in Sid that made the script all his own, that transcended his self-destruction. In his thuggish poses and rebarbative discourse, Sid now announces himself as a particular kind of English archetype – the stylised, intelligent hooligan whose sarcasm flays the established, the bourgeois and the boring, who tells a truth that this country never wants to hear.