AboutEssays2003Souvenir

“He owned nothing. No object, no family furniture, no souvenir. All he had was contained in an old trunk where he kept a few photos and notes relating to his past work.”

Lydie Sarazin, Marcel Duchamp’s first wife, from a privately printed memoir, published 1927.

This starkness of Duchamp is liberating. There is a similar resonance in descriptions of his New York apartment; one room, one chair, a basic bed, packing crate and two nails banged into the wall. A piece of string hung from one of the nails.

If it has nothing to look at, the mind has a better opportunity of being quiet. I don’t know if this was Duchamp’s intention, and pictures of his last home in Neuilly that he shared with his second wife show a much more ‘normal’ looking room. There are shelves and books, art and objects.

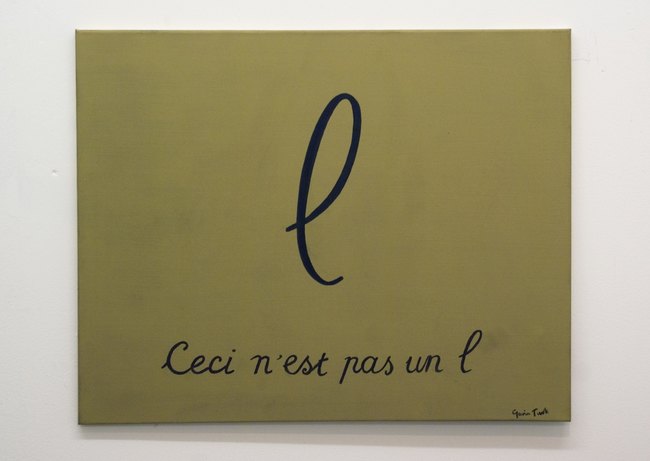

But a souvenir will trouble and disturb the mind. The word is French (it is a verb) and means ‘to remember’. The English noun ‘souvenir’ is the infinitive mood of ‘souvenir’ used substantively. The usage is modern. The word does not appear in The Bible, Shakespeare, Blake, Dickens, ‘Moby Dick’ or ‘Alice in Wonderland’. There is a souvenir in Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’ (once) and Scott Fitzgerald where usage is plummy and sentimental. Gatsby refers to a photograph.

“A souvenir of Oxford days. It was taken in Trinity quad. The man on my left is now the Earl of Doncaster.”

The etymology of souvenir is Latin from ‘sub’ meaning under or near and ‘venire’ to come. The meaning is of something, in this case a memory that comes from the deep of the mind. ‘Souvenir’ then describes an object that will dredge memory (like policemen looking for a corpse in the river).

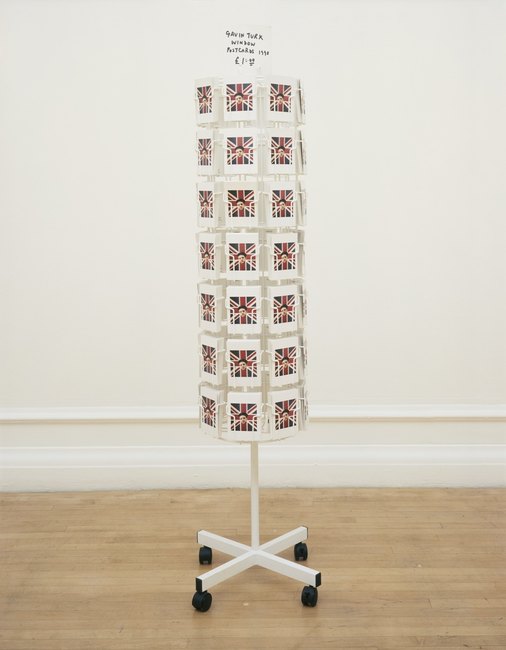

It is not common to think of souvenirs as objects that recall lost memory. In regular usage the word hitches itself to snow-domes and ‘tasteless’ (insists Wikipedia) objects linked to tourists sites and capital cities. It is possible these objects ridicule the colossal state monuments they miniaturise and recast in plastic. Or suggest that any place or object that requires a souvenir to remain memorable is therefore, by itself, forgettable.

But the souvenirs that recall lost memory externalise memory as three-dimensional objects. It is hard to see a memory. What does a memory look like?

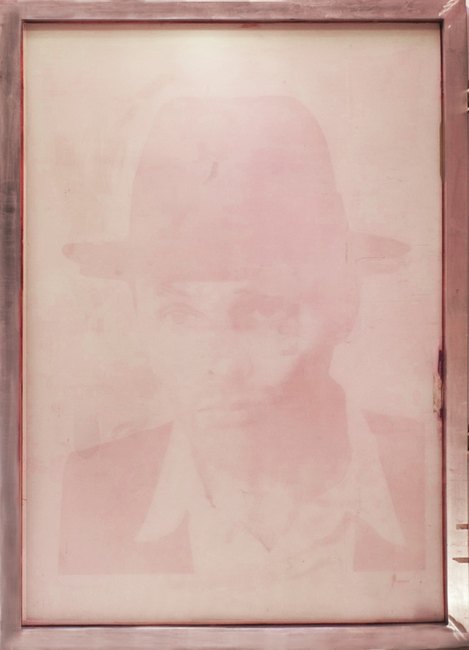

Pablo Picasso was fond of Alfred Jarry’s gun. Picasso acquired this weapon after Jarry’s death as a souvenir of his friend notes Duchamp’s biographer. (Although Picasso’s biographer Roland Penrose claims Jarry gave him the gun). Regardless of how he acquired the gun, Picasso took it on night-time jaunts and sometimes discharged the weapon in the Parisian air.

The gun reminded Picasso of his dead friend, say the biographers. It might be accurate to exhibit the gun and with the label ‘souvenir of Alfred Jarry, author of Pere Ubu’. It might be tempting to say the gun was a ‘relic’ of either Jarry or Picasso although the word ‘relic’ has a specific theological meaning.

“Orthodox Christians,” explains Bishop Kallistos Ware, “believe that the grace of God present in the saints bodies during life remains active in their relics when they have died and that God uses these relics as a channel of divine power, as an instrument of healing.”

And relics have a future. In the last days they will be reclaimed and refleshed by the resurrected saints. “The relics were the saint,” notes Patrick J Geary in ‘Furta Sacra’. But you could say ‘they are the saint’. They are not souvenirs. Or representations.

Jarry’s gun is inert. It does not belong to eternity. Jarry’s gun is not Jarry. It is a path to the memory of a dead writer (who will remain dead) and to Picasso’s memory of his friend (Jarry died in 1907, Picasso in 1973).

If Jarry’s gun still exists and if you could hold it in your hand it would be proof that Jarry (and also Picasso) did exist. It is an artefact or piece of evidence, like the dinosaur skeletons. And it can be difficult for those of us living in the present to believe the Past really happened. We need physical evidence; museums, galleries and archaeologies.

Jarry’s gun is like Coleridge’s Flower; an object that connects us to another world, in this instance Montmartre circa 1906-1910. Coleridge’s Flower is a meditation (unpublished in his lifetime) that reaches out to Heaven, Narnia and wonder.

“If a man could pass through Paradise in a dream, and have a flower presented to him as a pledge that his soul had really been there, and if he found that flower in his hand when he awoke – Ay! – and what then?”.

But most souvenirs, even if they function as evidence that you have been somewhere are ‘tasteless’ (says Wikipedia) and also kitsch. The word comes form the German ‘verkitschen’ meaning to make cheap and ‘kitschen’ to collect junk from the streets. Kitsch is the ‘commodification of the souvenir,” says Celeste Olalquiaga and ‘the souvenir the commodification of remembrance’.

There might be some who resist having their memories cast in ‘cheap’ plastic (and there is a reflex prejudice against plastic – Umberto Eco has written about the wonder and beauty of plastic).

St Mark’s in Venice is to be avoided, I was told on Boxing Day by a young postgraduate student of architecture, because it is tacky, a theme park. But if you walked away from the centre, my student friend advised, you will find strange, watery fields, real farmers, authentic experience.

This longing for the ‘authentic’ might traumatise an otherwise restful holiday. And there is an appalling egotism in the tourists’ refusal to accept his or her role. But this is a consoling delusion because (for some of us) commodified leisure and memory are harder to stomach than commodified transport or education.

There is an image Gavin Turk has exhibited of a discarded paper cup bearing the image of Stonehenge. And Stonehenge (says Wikipedia) is ‘one of the most famous prehistoric sites in the world’. I suppose you could say its the country’s oldest and most ‘magnificent’ art work.

Gavin may be having a go at English Heritage, who produced the cup because there might be some leakage, some diminution of value heading back from the cup to the ‘magnificent’ original.

But then again both the cup and Gavin’s image are perfectly adequate pictures of Stonehenge. And they are calm images. There is no anxiety about authenticity or form.

When I started this story I wanted to rail against spoons from Ramsgate and a Tower of London snow-dome; now I find myself warming to these objects; they are without angst and they are useless.

Celeste Olalquiaga, The Artificial Kingdom: A Treasury Of The Kitsch Experience (Bloomsbury, 1999)

Patrick J Geray, Furta Sacra, Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages (Princeton University Press, 1991)

Roland Penrose, Picasso (Granada, 1981)

Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp: a biotgraphy (H.Holt. 1996)