AboutEssays2003Trompe L'oeil

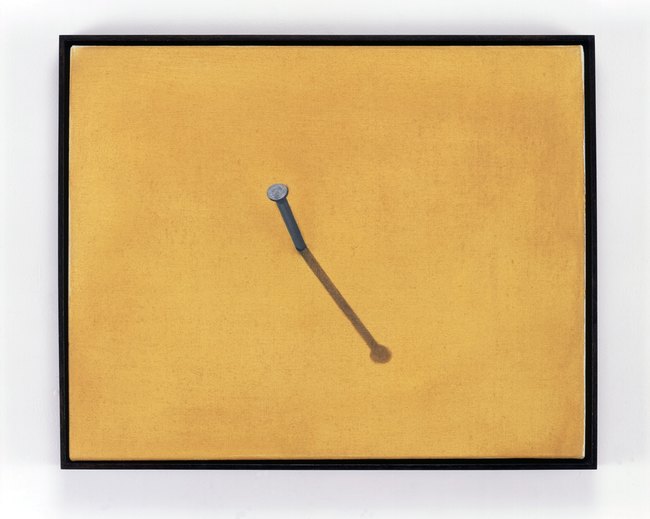

Like the carefully staged crime scene, trompe l’œil tricks the viewer through the arrangement of misleading appearances and false clues. Literally meaning ‘cheat the eye’, the art technique involves the realistic depiction of phenomena to create optical illusions, often turning flat surfaces into seemingly three-dimensional objects. Trompe l’œil art does not belong to a particular ism or medium but slips in and out of focus through the ages, depending on dominant regimes of representation.

Although the term was not coined until the early 1800s, the genre can be traced back to Greek and Roman times. The Roman writer Pliny the Elder writes of a rivalry in ancient Greece between the painters Zeuxis and Parrhasius, both accomplished in this particular art. Largely forgotten during the Middle Ages, the technique was given a new lease of life by the Italian Renaissance and the era’s advanced understanding of perspective, while painters of the Baroque era applied it to the then increasingly popular genre of still life. Artists of the Modern period, however, made limited use of trompe l’œil, as works no longer strived towards illusion or imitation but were made to investigate the grounds for art’s own existence. Nonetheless, a few painters, such as René Magritte and Jasper Johns, did appropriate the style and transform it into their own. The simulacral qualities of the technique, on the other hand, offered a desirable method for postmodern artists eager to challenge notions of authenticity, originality, and authorship.

Trompe l’œil is all theatre, which is another reason the genre did not catch on in the Modern period. In the late 1960s, the art critic Michael Fried objected to a turn towards ‘theatricality’ in sculpture and painting, a concept that, according to the author, betrayed the autonomy of the advanced, Modern artwork by turning the exhibition space into a stage of sorts. While Fried’s attack was primarily directed against Minimal art, art forms that use trompe l’œil may equally be added to his list of ‘criminals’, as they also trouble the borders between work, ornamentation, setting, and audience, and, like performance, depend on the actual, physical presence of a viewer to be complete. In other words, the ‘power’ of trompe l’œil is not inherent to the work but exists somewhere between image and spectator and between image and place.

At first glance, trompe l’œil art appears to have no author or origin; it aims to erase the traces of its own production. In the attempt to conceal the identity of the ‘perpetrator’, the signature of the artist may be hidden on an object within the image or, in the eighteenth century tradition, on a cartellino, a calling card or a note seemingly attached to the main work. Much like Edgar Allan Poe’s short story ‘The Purloined Letter’, the desired object is in full view but if we fail to recognise it as the thing it is, it inevitably falls outside our scopic register.

Trompe l’œil momentarily blends with its own surroundings and transforms the entire environment into a set of representations, causing us to question the validity of other appearances and confuse these with the main work. This is, for example, the case in chantourné, a particularly unsettling form of trompe l’œil where a painting is cut into the shape of the thing it portrays and displayed alongside actual objects. While this specific deviation was fashionable in the seventeenth century, more recent examples exist. Duane Hanson’s late twentieth century life-size human sculptures are, though not paintings, created in the same vein. These figures are so true to life that they have been known to trick gallery visitors who have believed them to be real and, on occasions, even attempted to talk to them. However, like the detective story, trompe l’œil hovers between suspense and surprise, and, eventually, incorporates its own slippage. This is what constitutes the paradox of the style: to be successful, it must involve its own failure and sooner or later give the plot away, which is why Hanson’s sculptures are crucially not human.

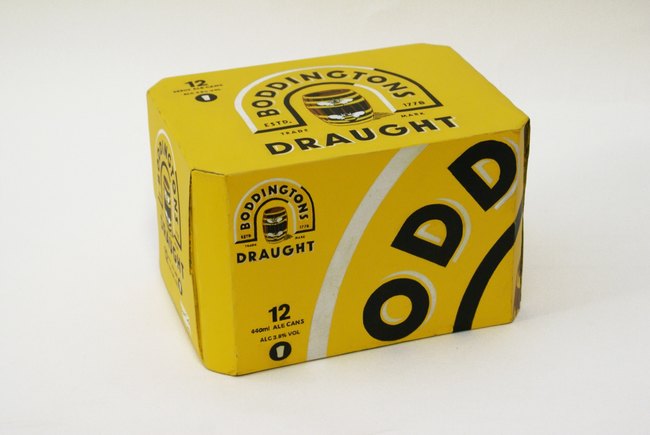

Still, some people are experts at turning themselves into trompe l’œil. This can make them seem untrustworthy, but such masquerading may also involve a critical element. La perruque is the French philosopher Michel de Certeau’s name for a specific performative practice through which the worker camouflages his or her own activities as work for the employer. La perruque can be as simple as a secretary writing a love letter at her office desk, a method through which, without being absent from her job or stealing anything of material value, she diverts company time. Such trickery is associated with the power of those who appear to have no power; it is a critique from below.

There is more than a phonetic resemblance between the word perruque, ‘wig’, and perroquet, the French term for ‘parrot’. While trompe l’œil appears to be all artifice, it strangely borrows a mode of appearance that we have come to associate with animality: mimicry, parroting, or aping. Closely related to trompe l’œil is trompe l’oreille, a ‘trick of the ear’. Here, a living being mimics the voice of another as decoy. Birds are masters at this art, and only the most experienced birder might be able to tell the difference between the call of the Pied Wagtail and that of a Blyth’s Reed Warbler impersonating a Pied Wagtail. Just as trompe l’œil erases the trace of its own author, so does trompe l’oreille, although in a different way. The successful avian impersonator throws its voice as if its call was heard from a distance, confusing predators both with regard to its kind and its whereabouts.