AboutEssays2008The Union Jack

Flags have always seemed, somehow, to accredit ‘ownership.’ Armies go to battle for the sake of their flags. They realize their defeat in the falling of their flag or their victory in the flying of their own. National flags are supposed to serve as the altarpieces of national pride, but the Union Jack seems to inspire a pervasive ambivalence in Britons today. Our National Flag pasted onto windows, fluttering from car aerials or hanging from balconies is becoming an increasingly unfamiliar sight. Looking closely at what our national flag represents, this is perhaps to be expected. Given the confusion that stems from generations of British imperialism, it is unsurprising that when our flag is flying high, no-one seems to know who or what it is supposed to represent.

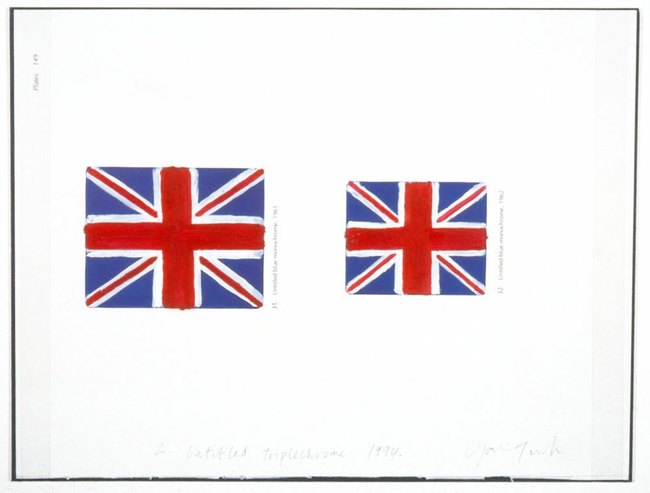

The lack of clear patriotic feelings in Britain is partly due to the hundreds of years of historical conflicts between England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland. England has notoriously colonized nations all over the world – and Scotland, Wales and Ireland have too suffered under this imperialist regime. Wales was part of the Kingdom of England when the Union Jack was first constructed in 1606, so the red St George’s Cross, at the time, represented both England and Wales. Then the St Andrew’s Cross – the white diagonal on the blue background – represented the inclusion of Scotland in the Union. St Patrick’s Cross – the red diagonal of Ireland – wasn’t incorporated until 1800. The Union Jack as we know it now was thus formed. Ever since, however, Scotland, Ireland and Wales have fought against this blanket ‘Britishness’ that the flag promotes, feeling perhaps that their own national identities have been usurped by the voracious colonizing appetite of England. This discontent has been channeled over the years through debates over the Union Jack’s composition – as if the flag in itself has come to embody this complex history of the ‘United’ Kingdom. The Welsh have made several attempts to try to include the Welsh dragon into the Union Jack to assuage their feelings of exclusion from it. Scotland has long since felt contempt that St Andrew’s cross is depicted behind St George’s. There is a suspicion in Ireland that the St Patrick’s Cross in the British flag was merely an invented convenience to fit the Union Jack, and has never been the National flag of the Irish. English ignorance of the Union Jack is captured by the stupidity of tourist shops in Oxford street in selling t-shirts depicting a Union Jack, brandishing the word ‘England.’ The flag has become, then, the flag of a divided Country, a country of split societies, none of which wish to harness the flag that tries to unite them all. The only people who seem to give any particular notice to our national flag are the very people who feel excluded from it.

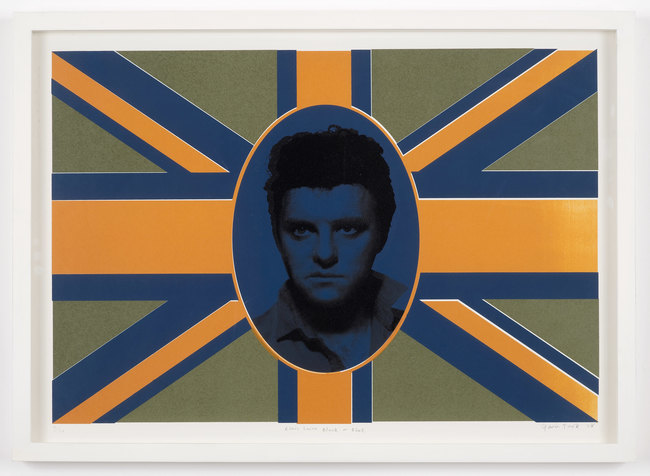

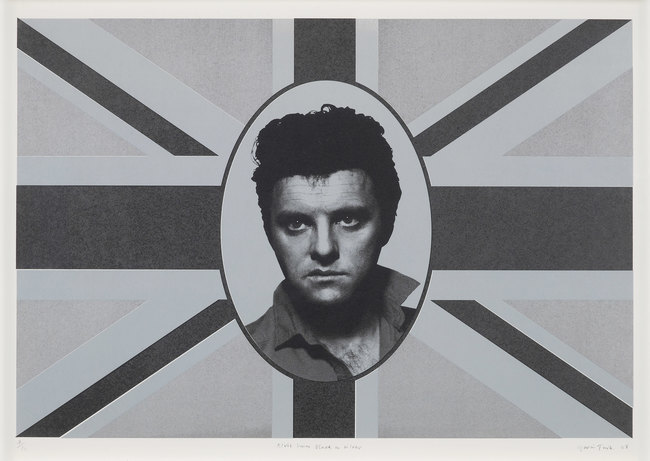

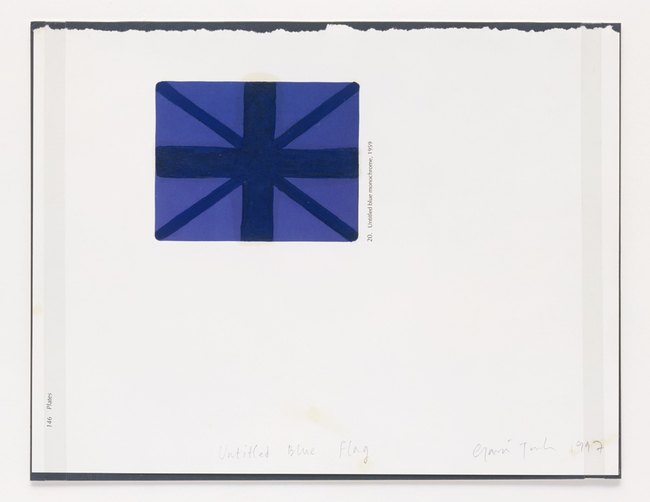

Wales, Scotland and Ireland have thus struggled to locate themselves within the flag – in the same way that black and Asian Britons have felt unrepresented by the Union Jack. It was recently proposed, for example, that black stripes should be incorporated into what was described a ‘racist’ flag. This comes into sharp relief in depictions of the Union Jack by black and Asian artists. These artists are giving voice to these zeitgeist issues, in an attempt to understand the multi-culturalist nature of post-colonial Britain. Again, people feeling marginalized, people feeling excluded from being ‘British’, voice this discontent through the symbolism contained in the Union Jack.

The National Front also saw the Union Jack as a representative of an exclusive white Britain, and they harnessed the flag as a symbol of white supremacy. The Union Jack became the flag of the National Front in Thatcherite Britain. Flags are supposed to promote nationalist feelings, which the National Front pushed into a violent extreme. The right wing National Front used the flag as a symbol against the multiculturalism that right wing British Imperialism set the way for. Britain today is coming to terms with the consequences of colonialism – a regret that it’s gone, an embarrassment that it ever happened. When ‘Britannia ruled the waves,’ the Union Jack was even coined ‘The Butcher’s Apron’. Perhaps part of the contemporary attitude towards the flag suggests our aversion to flying the Union Jack is due to an embarrassment about these imperial associations. Perhaps we don’t want to be reminded of the atrocities of our forefathers, the blood red of the St George’s Cross. Even today, the Union Jack can be traced around the world in the flags of the countries we ‘civilized’.

The red white and blue of Britain has fluctuated in and out of fashion over the twentieth century, not necessarily in parallel to national attitude. The Union Jack accompanied the Beatles on their World Tour of 1964 and soon became a rock’n’roll symbol of the artists and bohemians of Carnaby Street in the 1960s. As British pop music triumphed globally, the flag once again achieved the world respect it had during Imperialism. It became a marketing sign in the branding of the swinging city that was 1960s London.

The next decade saw the Union Jack ripped up and defaced by Punk. The inclusion of the flag on the album covers of the Sex Pistols together with the sarcastic patriotism of their ‘God Save the Queen,’ put the band at war with the establishment. The single was released during the time of Queen Elizabeth’s Silver Jubilee and it was seen as an attack on the monarchy. The fact that the band and their fans were brandishing ripped up versions of the monarchy’s own flag seemed especially pertinent. Like the artists, by defacing the Union Jack, punk bands of the 70s were voicing the concerns and dissatisfaction of a dispirited British youth. Again, the Union Jack becomes a symbol through which to speak. The flag represented the old school establishment and the flag’s vandalism heralded a new generation which went on to change the shape of the country.

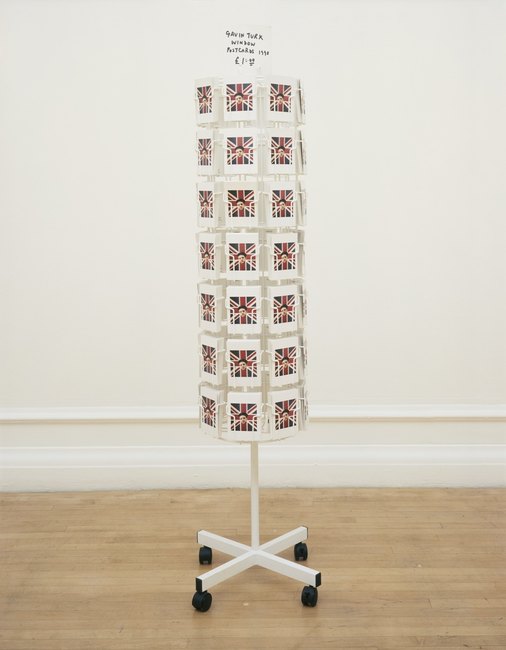

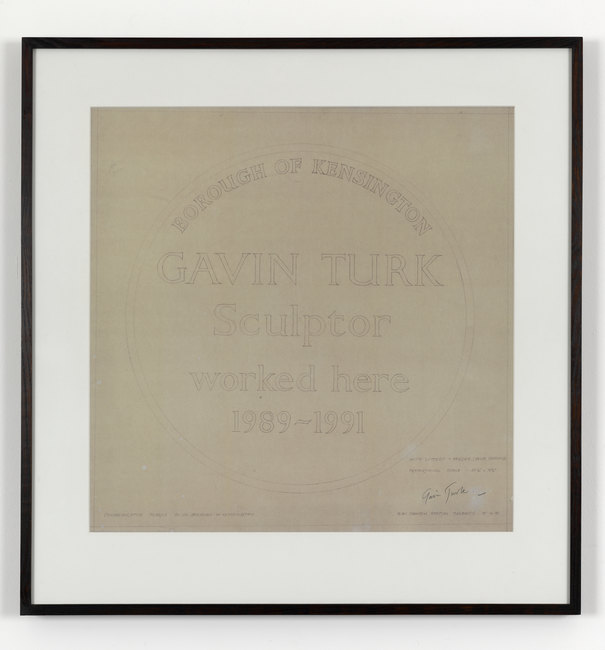

The late eighties and early nineties saw Britain again coming into the global frame that was seen in the 60s. Once again Britain started to dictate what was hip to the world, and this was especially true in the zeitgeist of the art world. The various names given to the art produced at that time, all further this brand in their reference to the fact that art itself was British: ‘Cool Britannia’ or ‘Young British Art’. Liam Gallagher and Patsy Kensit, the John and Yoko of the 90s, appeared in magazines draped in a Union Jack with the familiar headline of 1966 Time magazine, ‘The Swinging City’. Even Geri Halliwell showed her patriotic attitude as her Union Jack dress became one of the flag bearers of British pop culture.

However much the Union Jack has appeared in and out of vogue, there is still a marginalized interest and recognition in the country as a whole. The Union Jack has become a confused symbol of a divided nation, a nation to which no one really belongs. Jack of all trades, master of none…