AboutEssays2016Gavin Turk, POP, POP & POP

Thank you

A conservative critic got mad with Turk at an arts festival in Wales, in May, 20216. They were on a panel discussing contemporary art’s value compared to canonical masterpieces. The critic praised Matisse’s Red Studio but railed against Turk’s output over the years, the things he’d made that drew the attention of the mass media and gave him standing among curators and in the art market. He said everyone knows who Gavin Turk is: the artist who made a cast of his head using his own frozen blood. It’s another artists who did that but, even so, many in the audience rushed up afterwards to thank the critic. “It needed saying!” – was the general sentiment.

Rules

There is no absolute law of history and society that you can consult to see what everything means when you’re confronted by an artwork. You just have to arrive at your own thoughts. There’s always the knowledge, though, that these are being manipulated. You’re looking at something that takes its place in a history of manipulation.

Science

Is art a science? Is it a mistake to consider them opposites? Deconstruction says yes, while anyone today can say, “Sure, why not?” without feeling it’s end of the world either way.

Huffing and puffing

If you’re an artist, you can hardly not have noticed that making art is impossible without rules. A painting by Michelangelo of a snake and Adam and Eve is understood to be a vision the artist shad, which he simultaneously magically manifested in a tangible form on a ceiling. In reality he worked at it step by step for ages, trying, by thinking about the structure of art, experienced in countless artworks created by other artists, as well as the art he’d created himself over the years, to get the form to look effortless. He huffed and puffed all the way. Like Matisse, in fact, who was always trying to make effortless pleasure into a kind of principle of painting, and succeeded so much that people often imagine he really didn’t put any effort in. A rule in art is something like a structural idea, or a principle. It might relate to form or colour, for example. It might be a rule of animation for Michelangelo or a rule of simplification for Matisse. With Turk the rules are about ideas. In testing people’s assumptions about what makes art significant, he has to come up with a rigorous logic for every object, however incongruous or unlikely the terms of experiment might at first seem.

Popping

Rules of balance and harmony, which are timeless but also made up from scratch because new times require new means, inform Matisse’s The Red Studio as they inform works of the High Renaissance, and a picture by Turk of a pop gun.

Ordering

To remain with the rule issue for a moment: we should get it straight about one thing – there’s no set of rules that says how to make the perfectly efficient artwork, that artists have either carefully studied or carelessly only read a few and tired busking instructively to make up for not knowing the others. Instead, and this is certainly something we can see operating through Gavin Turk’s output, a work is made that eventually achieves its own order, and understanding anything much at all about the work, if you’re the viewer of it, involves perceiving that order.

Order of Pop

Things about a sculpture called Pop Turk created years ago, are ‘just so’ – the balance and order of its various elements. But they probably weren’t entirely pre-calculated. A precision of association, fantasy, memory, collective desire, and tangible physical properties (all materials Pop is made from, and the particular way they’re arranged) was achieved eventually by a process of trial and error – it’s remarkable that he came up with it so early, though, as it can often seem like a dictionary of all his ideas.

Garbage heap of despair

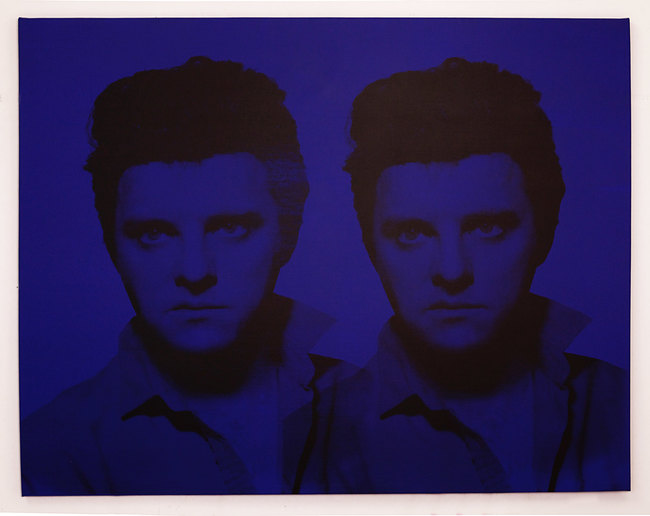

Pop featured a clothed dummy in a glass case representing Turk himself, with his own ordinary features, performing the role of Sid Vicious the iconic punk. Sid in reality was a rather beautiful figure, whose iconic meaning includes Sid’s own self-image as discarded flotsam on society’s garbage heap of despair. In Pop Turk equals Sid and both of them multiply into Elvis, because Sid is posed as Elvis as he appears in a series of paintings created by a great master of Pop.

Warhol

Turk, Sid and Elvis: they suck the milk of their artistic mother, Andy Warhol. Warhol’s paintings on a silver ground of Elvis posing with a gun, are confusing because it’s clear they’re really photos, and he didn’t even take them. It’s a Hollywood production still that promotes an Elvis movie. But Warhol did of course take photos and even make movies. But they’re confusing, too, because they question skill, authorship and even meaning.

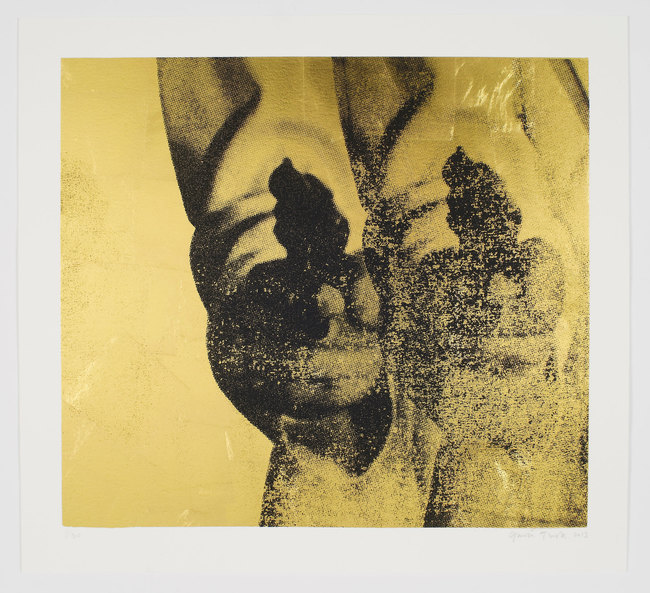

Double

Pop’s meanings are elaborated and condensed in this show by silk-screen paintings entitled: Double Blue Elvis, Double Pop Black and White, and Double Gold Pop Gun on Linen. Turk takes Warhol, the history of Punk and his own self-questioning self-analysing the role of a falsely exaggerated glamourous self in society’s most recent phase of exalting art – and transforms them all into the medium of confusion about authorship and authenticity that Warhol worked within everything Warhol came up with.

Theories

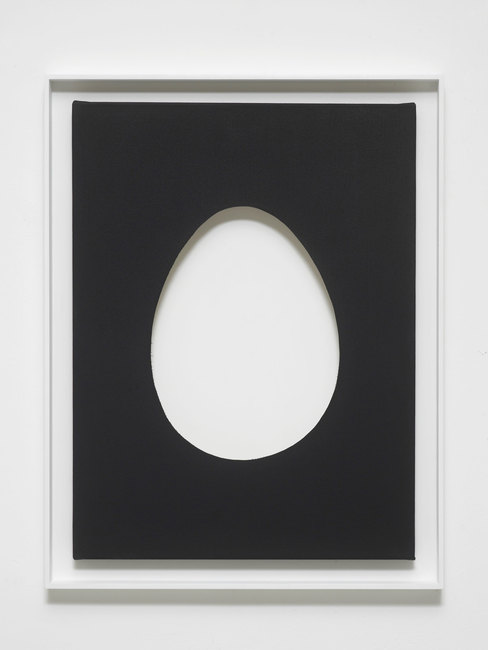

What’s happening when you see a garbage bag hyper-realistically made, so it looks exactly like a garbage bag (American Bag). Theories of representation could tell you. What if it’s an egg shape cut out of a dark-toned canvas so the hole, with the white of the wall behind shining through looks at first actually like a big white egg (GT DAD EGG). The psychology of perception could be helpful in this case. Be careful not to get lost, though. Illusion might be the thing, and psychological perception. But identity is it, too. And appropriation and celebrity – Turk appropriates the forms of artists who have pioneered forms or broken forms down (pioneering doubt). He looks at the cult of the artist as celebrity, shoring it up to break it down.

Your own direct thoughts

What about just having your own direct thoughts? You’d need some familiarity with the art scene, so they wouldn’t be totally direct. But anyway, yes, your own thoughts and your familiarity with art are enough. Enough for what, though: understanding trust? What if the work you had to think about was a realistic representation of a fire lit by the homeless lonely outcasts, loveless bums – to keep warm (Burnt Out), or a polystyrene cup with a tea stain on it (Conversation Piece) or a chewed apple core (Hunt’s Duke of Gloucester). Would you feel button-holed, as if art is demanding you do a bit of moralizing and reflect on all the overlooked things of this world, including life’s human rejects?

History of Art

The garbage bag sculpture and the negative-space/egg-shape painting both involve simple tricks; each offers a different kind of illusion. At the same time, they take their place in a history of forms. Photo-realism and Hyperrealism, the photographic-looking paintings and 3D objects of the 1960s by figures like Chuck Close and Duane Hanson, are behind both works. But these lead also onto a much larger notion, seemingly timeless, but having all sorts of actual origins, of art as a direct picture of reality (almost magically summoning it up): art picturing the world; and the measuring of the achievement of a particular work of art according to a scale of how much it looks like reality and how much it falls short of looking like it. “That cut out hold looks like something solid! That painted bronze looks like a garbage bag!”

Shaman

The bigger picture of the history of art over all of time, which Turk’s exhibition in Knokke features in, extends as far back as the smoking oil lamps held by shaman types, certain elected special representatives of groups of cave people, as they crawled on their bellies through tunnels to get to opened-out spaces within a mass of rock – pitch black, their lamps lit them up with dancing shadows – where they painted magic animals the group wanted to kill or worship. Then the pictures rush up to our own moment, the flat transparent plane all our noses are press up to now.

Medium

This immediacy of all the thoughts we’re conditioned to have about contemporary art, whoever’s doing the conditioning – the manipulators, the represented elect right now – is almost a medium that Turk works with, or a constituent property of the medium of confusion about truth that he inherited from Warhol and Conceptual Art.

What is a form?

In art a form is a collection of parts that makes up a unity – the unity is the form. The history of forms is a history of unities. We see the history as progressing or else just altering, or even having a random structure, or one that is over-determined, possessing innumerable possible different causes. These formal unities are visual and psychological, but also social and cultural. Everything, in fact, is behind them or in them, or can be accessed via them allegorically or metaphorically.

Rubbish

A form can be unattractive or compelling because it ought to be unattractive, but you stare despite that knowledge. You might look at a tied-up full garbage bag in an art gallery and think, “I don’t want to look at that.” Maybe you wonder what it is you’d prefer to look at and the thought occurs, “A sensitive painting”. And now you see used paint tubes and even an artist’s palette in need of scraping: here they are in the same exhibition. And also, they’re even some paintings. But they have holes in them, like Fontana. And then if you squint enough, and peer enough, you see the holes are arranged to indicate the letters G and T, the initials of Gavin Turk.

Overlooked

A homeless person’s sleeping bag. A garbage bag with its string tied. He’s made art in the past based on both of them, with the same method, a technical perfectionism that highlights looking even as it questions it: there’s nothing to see here.

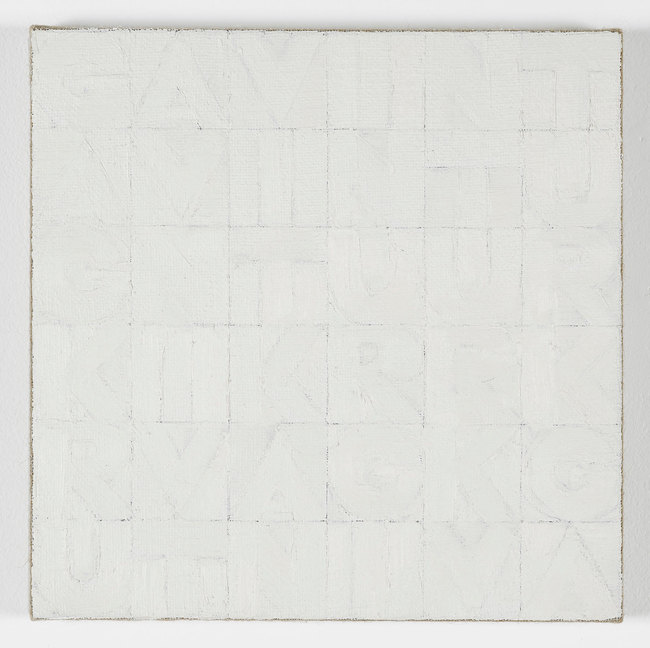

It makes you think

There are paintings showing Andy Warhol in his last famous self-portrait series, the hair of his wig flying outwards as if he’s been electrified, but with Turk’s face instead of Warhol’s. And paintings that immediately recall Alighieri Boetti’s woven coloured objects with letters of the alphabet, but spelling out repetitive anagrams of Turk’s name. In this show are images and objects with letters of the alphabet but spelling out repetitive anagrams of Turk’s name. In this show are images and objects that can be sense to be in different categories, and also the categories can be scrambled, but above all there’s a category that keeps returning, a common ground of the common itself, the banal. Overlooked junk and trivia. We consumer stuff, we throw its remains and husks away and we don’t think about them. We’re destroying ourselves, we now realise, without wanting to think about that either. We go to art galleries, and we congratulate ourselves that we’ve been made to think.

Ordinary objects

The ‘ordinary’ can be art’s subject or it can be an issue it deals with (think of all the religious art that transforms it). Surrealism makes it menacing. Realism makes it attractive romantically, it foregrounds a romantic ideal of the normal. But the ‘ordinary’ is hardly ever not there in art of any period. Even the earliest focused on the beings Man knew as an everyday presence, his neighbours the ordinary animals. And with Turk the ordinary is nearly always central. (It might be an exocytic Conceptual Art reference but it’s ordinary to think about copying it and seeing what will happen). Often his ordinary objects are made of cast bronze, the surface painted with an eye-fooling illusionistic precisions, so you could easily never know their true nature.

Striped pole

The opened-out spaces in the mass of rock the cave artists drew bison and mammoths in, gives way to the Venice Biennale and the Basel Art Fair. Also, the four yearly Documenta, with its solemn historical greatness, a particular year of which (1972) Turk invokes with his multiple bicycle artwork that pays homage to the conceptual artist, André Cadere. They’re going to be on a rack outside the gallery, and anyone can ride one. I had to scratch my head to remember Cadere’s works, wooden poles of various widths and lengths, clad in wooden spheres with a hole in the middle, each painted in a contrasting flat colour and the colours arranged so the whole unity conformed to a certain mathematical system Cadere was fond of. They look like stripey poles. They constituted a sort of conceptual art version of paintings where, because he could carry them around and put them in exhibitions and just pick them up and take them out again if he wanted – or carry them around the streets and become an exhibition of paintings just by walking along – a lot of things about painting as a historic form could be challenged. In a funny logical proposal, foolish and profound, property ownership, stability, continuity and money were all challenged. All the elements required for a painting are present (a form, some colours, some shapes, an arrangement) but fundamentally altered. He often referred to them as “limitless painting”.

Train

Cadere agreed to walk from Paris, where he lived to Documenta in Kassel, Germany. The Documenta director that year, Harold Szeeman conceived the walk as a significant re-enactment of a great event of 1904 in which Brancusi walked from Munich (where he was living) to Paris, at that time the centre of art. Cadere mocked up some postcards to indicate towns passed through on the walk, arranged to have them posted at convincing intervals, and then took the train all the way. Incensed at Cadere’s impurity when he found out the deception, Szeeman barred him from Documenta, but he showed in it anyways, became a legend and then died young in 1978 at 44.

Authority

The mythology of Cadere’s activities in 1972 is empty without the ingredient of its main background feature: the particular art-cultural quality of that time. Its revolutionary tone comprised many originating voices and ideas, but prominent among them was Guy Debord and his book of Situationist refusal of authority, The Society of the Spectacle. It was published in the year of Turk’s birth, 1967, and it introduced the world to derive and the detournement. These were methods of revolutionary play: drifting through the city obeying internal impulse, not being directed by authoritarian forces; and re-wording popular comic strips so their content jumped register from obeying consumerism to understanding revolution.

Recycled

Now Turk brings all that round again in the least revolutionary of times, although perhaps they hold some positives progressive surprises for us yet. This might be the thought as visitors to his show meander pointlessly round Belgian streets on stripey bikes. You can get somewhere, a transformed reality, directed by nothing but your unconscious.

Meaning of Meaningless

Gavin Tur, Sid Vicious, Elvis Presley, Andy Warhol: overlapped, layered and multi-levelled, like tracing paper, onions and car parks – where exactly are they all and how are they intersecting? What is the metaphor, what is the special effect? The low and the high, the normal and the conceptual, the heightened and the unseen, the unseen becoming not only noticed, but spot lit and the lurid glow understood as something important in itself, meaning of meanings. What happens with contemporary rat, how does it show us value, what skills are involved, how do we appreciate them, what skills do we need ourselves as viewers to know what we’re clapping for? Shouldn’t it just happen anyway as with Shakespeare’s great art of humanity? why does a category exist for ‘contemporary’? Is it an apology or bragging?

Turk’s first Pop

When Turk first has an exhibition outside an art school it was an impressive affair considering no one had heard of him until this moment. He was in his early twenties and the dealer Jay Jopling was attempting to introduce him to an art audience. In 1993 the climate of art in Britain was pervaded by images and ideas of celebrity. It was as if until just recently contemporary art had been nothing to society, or very little. And then suddenly it was at the centre of it. But society was still thinking in the old nothing way. And celebrity was the only value it could come up with to explain the move whereby art’s former obscurity could now be perceived as glamourous instead of hateful. Turk’s show was all about it, but in the way the sound of My Way in the 1979 film, The great Rock and Roll Swindle, is all about it. How can a liquorice pipe that is actually a bronze object carefully painted to resemble a popular sweetie, signify? It does it in the way Magritte’s pipe that isn’t one does it, by setting up comic philosophical agonies: endless echoes of “What am I?”.

Comic bullet

In his first exhibition in his studio in Charing Cross Road, a comic Warhol, Elvis, Sid Vicious and Gavin Turk compressed into a single mannequin stood in a glass case holding a popgun, within a warren of spaces, corridors leading to joke enigmas, sweeties saying, “Nothing to see here”.

Economy

Deregulation, privatisation, and the opening up of markets everywhere, since the 1970s, produced a money society. The rich understood with a blast of wisdom like a thought striking a Biblical prophet, that money spent on social services was actually money waste. As Fredric Jameson puts it, they had to put the extra wealth from saved taxes somewhere.

Life

The place they chose turned out to be stock markets. (Hedge funds are a form of insurance in the playing of the stock market). This global casino of pure financial gambling is now well known as the background to all our lives, generating meaning, explanation and law.

Laughing

The depraved ravening marauding Nero, Tiberius and Caligula of the misty past, became our fellow societal members, laughing and sneering when we express puzzlement at them sucking our blood. It became culture’s job to process the pure Darwinian system that everyone’s now signed up, willy–nilly, to live by. The fittest serving, as the rule of existence, found its parallel in art as celebrities scandalising.

He worked here

Turk’s first dealer, Jay Jopling, told everyone he became certain Turk was star material when he saw the only object that comprised Turk’s Degree show exhibit at the Royal College of Art. It was a British heritage plaque. Otherwise, the whole space was a whitewashed emptiness. The event was titled, Cave, after Plato’s allegory of the search for truth. (We think we see it when it’s only shadows on a wall). The famous generic circular sign, high on a wall, with its tasteful Wedgewood-like colouring, mid-blue with white lettering, announced: ‘Borough of Kensington, Gavin Turk. Sculpture, Worked Here 1989-1991’

Uh?

As it happens, Turk was puzzled at Jopling’s saying this because the whole point of the gesture (which actually caused him to fail his degree) was to question the star system not celebrate it.