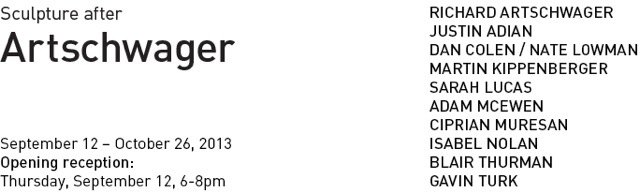

Exhibitions2013Sculpture After Artschwager

Sculpture After Artschwager

12 Sep 13

David Nolan Gallery

David Nolan Gallery is pleased to present Sculpture after Artschwager – an exhibition which examines the diverse legacy of American artist, Richard Artschwager (1923-2013). On view from September 12 through October 26, the show brings together 10 artists whose work testifies a relationship to his highly original output.

Artschwager came of age as an artist during the early 1960s when a new generation of sculptors were having their first exhibitions in New York City. Notable among these were Robert Morris and Donald Judd, whose measured geometric forms would eventually become labeled under “minimalism”. Artschwager exhibited alongside these artists in a 1966 sculpture survey at the Jewish Museum, though his work – a sculpture of a table, rendered in formica – was set apart for its kitsch materials and light-hearted humor. This playfulness and humanity, which runs throughout Artschwager’s practice, is what distinguishes him from many of the artists who were making work in wake of modernism.

In this exhibition, we assess a number of Artschwager’s themes and formal innovations, which we trace through a variety of younger artists who are working currently. One exception is a sculpture by Martin Kippenberger (1953-1997), which was first shown in an exhibition entitled A Man and His Golden Arm (in our SoHo gallery) in 1994. This work is comprised of a wall-mounted wood and bronze relief affixed with 34 colored objects. On the floor below is a shipping crate, whose unusual proportions are designed to accommodate the piece above. This self-conscious announcement of the work of art as a commodity relates to a concurrent body of work in Artschwager’s practice (which, by coincidence, was presented the same year at another gallery in New York) wherein finely crafted wooden crates confounded the typical expectation of “art”, offering a witty take on the art market and the impulse to collect.

Artschwager’s groundbreaking discovery in the 1960s was the use of commercial-grade products as possible materials in art. Many of his paintings made use of Celotex (designed for ceiling insulation), which lent a peculiar patterning to his pictorial surfaces. The use of formica was another interesting innovation, as it involved the transfer of a two-dimensional surface – often a photographic representation of wood – onto a three-dimensional object. This relationship is developed by British artist, Gavin Turk (b. 1967) whose bronze sculptures of ordinary objects (a cardboard box, a car tire) are meticulously oil-painted, in effect re-animating the traditional idea of the “trompe-l’oeil” within in a three-dimensional realm.

Gavin Turk has described “the overt recognition of what we are looking at” in relation to Artschwager’s sculpture: recurring objects – tables, doors, mirrors or a basket – are articulated thorough stylization and an economy of means, often to a point of caricature. Jennifer Gross characterizes these objects as “protagonists in Artschwager’s pictorial/spatial drama” which exist in “a world of surreal banality through which he thoroughly investigated the boundaries of a room inhabited by familiar things”. This exhibition extends on this spatial drama, casting various uncanny objects from everyday life into an unusual stage show. Adam McEwen’s (b. 1965) Rolldown Gate could be a conceptual stand-in for an Artschwager door – instantly recognizable, but also surprising – while Isabel Nolan’s (b. 1974) Invisible Mirror re-invokes Artschwager’s versions of the mirror motif.

Towards the end of his career, Artschwager turned his focus to images of an open road leading out to a horizon. Blair Thurman (b. 1961) touches on this theme, as do Nate Lowman (b. 1979) and Dan Colen (b. 1979) in a collaborative piece. In each of these works, road imagery is enlisted in the making of highly original sculptures.

Finally, the exhibition introduces the work of Justin Adian (b. 1976), whose unusual wall-mounted sculptures recall Artschwager’s radical “blps”, which, seemingly useless, appear in unexpected places. Adian’s sculpture – essentially a painted canvas, stretched over a strangely shaped support – resides in the corner of the room (a favored placement for Artschwager). Its brightly keyed yellow was also an important color in Artschwager’s work, featuring in the formica pieces of the early 1960s and in the wild and imaginative landscapes drawn at the end of his life.